The residents of the interior regions of Visakhapatnam in India depend to a large extent on ganja cultivation to survive.

By Paul Oommen

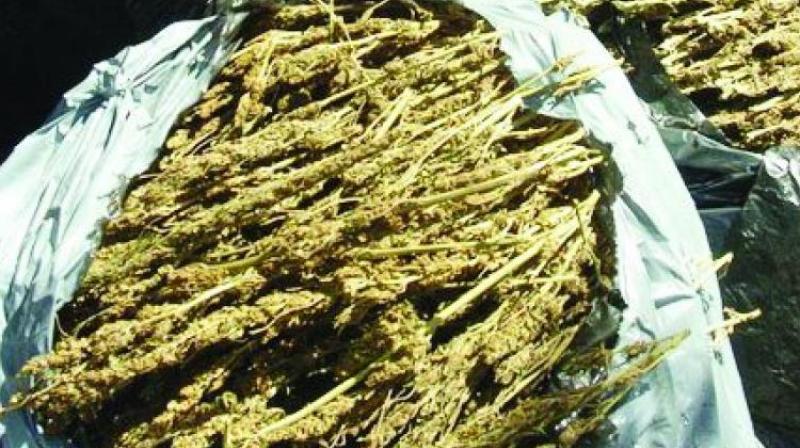

Around 20 km from Chintapalli town, in Andhra Pradesh’s Visakhapatnam district, 30-year-old Chittemma* (name changed) and her family members are busy rolling green leaves into small bunches and then placing them to dry on an old blue saree. They’ve recently started growing marijuana — or ‘ganjai’ as it’s locally known — inspired by others in the village who have made a steady income from the cultivation. Right beside the blue saree is a black sheet, with almost-ready dried bunches of ganja. “It still needs to be dried for another three days and then it’s good to go,” Chittemma says.

In many other homes in the tribal hamlets in the interiors of Chintapalli, and all around Chittemma’s hut, fresh cannabis plants stand, swaying to the wind. But there’s also worry in the air. “We put all that we had to scrape together Rs.50000, in order to cultivate 50 ganja plants. Now we’re told the police are out to destroy them,” Chittemma says. “One set of plants have been harvested but many more are not yet ready for harvest. We’re hoping they won’t come all the way to our hamlet… We’re trying to dry what has already been harvested so that we can save at least this set of leaves,” she explains.

The residents of the interior regions of Visakhapatnam — also known as the ‘agency’, after the Agency Act passed during the British regime in the Madras presidency — depend to a large extent on ganja cultivation to survive. They know it’s illegal, but most years the police and the state have ignored ganja cultivation. Ganja also fetches them an assured good income, unlike other crops like pineapple that is also grown in the region. But with the Andhra Pradesh police cracking down on ganja cultivation with Operation Parivarthana, people are worried.

Ganja cultivation a way out of poverty

Ganja cultivation a way out of poverty

“Cultivating ganja has given the tribal residents of the region a way to survive,” says Khasim Valli, a journalist who works in this area. According to social activists working closely in the agency areas, almost all women and children in the area are malnourished. “The iron percentage of the people in agency is below 7, which renders them anaemic,” says M Malini, who has been working in the region with an NGO for around 25 years.

“Most tribal families live in abject poverty. They work each day only for their survival. They eat a ragi porridge called ambali and try to sell most of their produce. With rampant malnutrition and lack of access to healthcare, for a child to survive in the agency areas is a matter of luck,” Khasim explains.

“With the money that these areas earn from ganja, we have witnessed rapid change, especially in the last 10 years. The Rs 1.5-2 lakh that they earn from one harvest of ganja helps them survive comfortably for around two to three years,” Khasim says.

Chittemma and her family reside in a tribal hamlet that is home to families that belong to a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG), local to Chintapalli mandal. PVTGs are the most backward among the tribals. The members of this group don’t have access to education, and survive by growing their own food. They collect forest produce and sell it in the local market every week. According to the latest data sourced from the Andhra Pradesh Integrated Tribal Development Agency (ITDA), 28% of the tribal communities consist of members from PVTGs.

The lack of opportunities has meant that the residents depend on ganja cultivation — and the climate, both natural and political, has been helpful. The cold weather in the agency areas and the mist in the mornings make it perfect for growing ganja plants.

The inaccessibility, the favorable weather conditions, and the presence of Maoists in these areas make for a perfect recipe for ganja cultivation. Out of 2,160 tribal habitations in the 11 agency mandals of Visakhapatnam, 569 habitations do not have access to a road. Only 886 habitations have only a katcha road that leads to their hamlet. People have to trek very long distances to reach these areas and hence police presence used to be rare in these regions. With most hamlets not having street lights, what remains of the roads in the entire agency area slip into pitch darkness after the sun sets.

It takes about an hour to reach Chittemma’s hamlet from Chintapalli town. The route is filled with potholes and puddles, making the journey arduous. While the local residents use bikes to ferry people, our car makes people take notice.

Usually, vehicles come into these interior villages with ‘customers’ — smugglers who travel from across the country to procure ganja from the hills of Andhra and are part of the distribution networks in the cities. Chintapalli, Paderu, Sapparla, Koyyuru, Gudem Kotha Veedhi (GK Veedhi) and Madugula mandals are other locations where customers head to for procuring ganja in bulk. In Chintapalli mandal, they get in touch with agents and brokers who meet them in the town. These agents/ brokers are said to be highly influential, with good connections with the farmers and also the police. They know exactly where ganja is being cultivated and how much is available in each plot, and take the customer into the interiors.

Ganja is grown around June-July and is harvested within five or six months — between November and January. Some customers visit even before the cultivation and hand over seeds, fertilizers and other requirements to the farmers, and then return only when it is time for the harvest. Some other customers come directly during the harvest season and are taken to various fields to choose from, and then strike a deal with the farmer for the entire produce.

The farmer’s responsibility ends once the crop is handed over to the customer. The broker’s responsibility ends when the customer crosses Chintapalli with the procured ganja. Outside Chintapalli, how the customer manages to cross the police checkposts while descending the agency areas is strictly his responsibility. The broker is given a percentage of the procured produce for his efforts in coordinating and connecting the customer to the farmer.

Astounding prices

“We cut the plants, dry them and then hand them over to the customer. The customer gets his people to load the produce into their vehicles for transport,” explains Ramanna, a tribal residing in the agency areas.

The farmers sell ganja according to a local measurement called ‘veesa’ — 1.4 kg makes one veesa. The measures that were in use before the metric system was introduced continue to be used here. “We get around Rs.400-500 for a veesa of ganja,” says Ramanna, “Altogether, we end up making around Rs.1.5 to 2 lakh in one season, depending on how much has been cultivated.”

When asked if he knew how much the same would fetch in the city, Ramanna says, “We don’t know, we don’t want to know either. We’re getting a very good price, which no other crop fetches. We’re happy and satisfied.”

The numbers though are astounding. The 1.4 kg for which Ramanna gets Rs.500 would fetch anywhere between Rs.30000 – 70000 in cities, depending on the quality. The price of ganja gets escalated to unbelievable levels because it has to pass several layers of middlemen, security and checking.

How the ganja is transported

Once the transaction is done, the buyer is left with the arduous task of getting the ganja transported to different destinations. The first part of this drive is to leave the agency area without being caught at the checkposts.

According to insiders, smugglers often deploy young men from tribal areas, luring them with expensive bikes and perks as remuneration, to ride as pilots ahead of the vehicles carrying ganja. The role of the youth on the bike is to keep an eye out for checkposts and alert the vehicle, which follows him at a safe distance, in case of any checking. As soon as the pilot notices a checkpoint, he tries to call the driver of the vehicle. If the call doesn’t go through, the pilot takes a U-turn and heads back to alert the vehicle.

The entire transportation process is usually well-chalked out and planned meticulously. The route from the source to the final destination is considered as layers or orbits. Often, multiple people are involved in each of the layers, and with each layer passed, the price of the ganja increases due to the risk involved in transporting it. There are well-connected and influential middlemen too involved in these layers — their job is to save the smugglers in case they get caught by the police, allegedly by greasing the palms of those involved.

Local residents reveal that most often the smugglers manage to get through the checkposts as they make special boxes inside or at the bottom of the vehicles, which are loaded with ganja. The boxes are concealed and not visible in the checks that the police carry out.

A police officer who had served in the agency areas in the past tells that most often it is impossible to find out which are the vehicles smuggling ganja to the plains. “We get inputs from our sources that a vehicle with ganja is passing. We then heighten security and check thoroughly. Without leads, it is really difficult to find ganja being transported. Only those with years of experience can make out the presence of ganja,” he says.

Reliable sources say that “friendly” policemen posted in agency areas are given a good share of the profits to ignore the smugglers. “Just to show that the police are doing their job, once in a while they seize a small part of the entire bounty and allow the smuggler to leave with the rest. They then show it to the media and announce that ganja has been seized,” a journalist who closely covers the region explains.

With the increased surveillance though, the smugglers also try to offer a few thousand rupees more to lure farmers and their families to transport the ganja. The farmers are made to carry the product in bags through the forests, confirm Paderu MLA K Bhagyalakshmi and other senior officials in the Police Department. “The checking is usually less in the forests and they slip through. The tribals fill ganja in bags and carry it on their shoulders. Their job ends once they hand over the bags to the person at the end of the forest area,” MLA Bhagyalakshmi tells TNM.

Masterminds behind drug trade still at large

Masterminds behind drug trade still at large

Quite often when ganja is caught, investigations reveal the roots of the nexus are in the various mandals of Visakhapatnam agency. Many of the people caught by the police have not returned because they continue to languish in jails due to serious non-bailable sections slapped against them. However, they are easy targets, people who are trying to earn a livelihood by cultivating something that has a market. But who are the masterminds behind the drug trade?

The police say they’re clueless.

Even while the enforcement drive continues in full swing, social activist Malini says it will not help end the ganja nexus in the state. “The nexus is too complex and will not die down so easily. The police and the big business agents will continue to exploit the tribals and lure them with money and incentives to get their job done. While this happens, the police will catch the poor tribals to show that they are also doing their job while the big tycoons get away scott free.”

The way forward

The Andhra Pradesh ITDA sees the issue of ganja cultivation in the region from a social, economic and developmental angle. The ITDA Project Officer has come up with a Rs 50 crore proposal to offer alternate crops to ganja and seeks monetary support from the government to help farmers switch to horticulture and agriculture.

The new proposal pitches for 100 acres of litchi, 100 acres of dragon Fruit, 250 acres of pineapple and 500 acres of ginger. If approved, the agricultural crops will include 2,000 acres of groundnut, 5,000 acres of niger, 20,000 acres of finger millet and 10,000 acres of rajma. The Rhythu Bharosa Kendras will ensure a good price for the farmers.

While the new proposal is taking shape, it remains to be seen whether the state government will accept it and provide the ganja cultivators more support to mitigate the crisis at the root level. Though Operation Parivarthana has put an end to the ganja business this season, until the government seriously considers options to help the tribal farmers, they will certainly be inclined to grow ganja as it has a sure market — something no other crop like pineapple, turmeric or coffee cultivated in the hilly terrain can guarantee them.

_________________________

Courtesy: The News Minute