My father, my grandfather and my great-grandfather spent their entire working lives in the Dutch East Indies, as Indonesia was called until 1945.

By Tulsi Mohinani

At home in the world

We Bhaibands adapt to any country we settle in and soon develop love and loyalty for the country which gives us our livelihood. Anywhere we travel, we soon feel at home because someone we know lives there, a relative or a friend who will welcome us and make us feel at home. In a way this means we are citizens of the world and there is no strange place. It may be a different place but there will always be a home in that new place. Or we can always build a home in that new place. I have done so, and when I moved on, I always left the past behind without regret or longing. The only country I’ve thought back about is Indonesia, maybe because of the happy childhood memories. It is now 34 years since I came to live in Chile, the most beautiful and welcoming country in the world, which gave me and my family our home.

Today, my parents are no longer with us; my brother Jiwat and sister Chandra are also no more. Mohini, our eldest sister, lives in Pune. Haresh and Ramesh both live in Hong Kong, with their own multinational businesses which they run along with their sons, just as my son Sanjay works with me. Lacha is in Malaga, Sheila in Santiago, Pushpa and Ishu in Grenada and Babe in USA.

The bonds between us are strong and we have passed them on to our children and their children. Our parents’ blessings are always with us. Though we live in different corners of the world, we are in constant touch and we meet as often as we can.

Hardwar: Exploring our roots

I lived in Sindh only for the first year of my life, and have no memories of it. However, I do have strong feelings for those of my community who had to leave the land of our ancestors so abruptly and with no possibility of ever going back.

When I was young I loved to travel, and came to realize that this was a trait I had inherited. My ancestors had been great travelers, adventurers who never let borders restrict them. In their time, travel was tedious and strenuous, and often dangerous too. Yet, they spent their lives in distant lands, with little or no communication with their loved ones at home. I sometimes wondered who these daring, adventurous people were who left their homes to seek their fortunes in faraway lands. One day, completely by chance, I found that they had indeed left a small record of themselves.

I was in India on a buying trip in mid-1998, travelling with my Mumbai friend and supplier Jagdish Daswani. From Delhi he suggested that we take a day or two off to visit Hardwar, and I agreed. Hardwar is a place on the river Ganga, considered to be one of the holiest cities in Hinduism, and is traditionally one of the places where families bring the remains of their dead to be consecrated. To be honest, I went more out of curiosity than as a pilgrim, but that did not stop me from having a ritual dip in the Ganga to wash away all my sins—just in case.

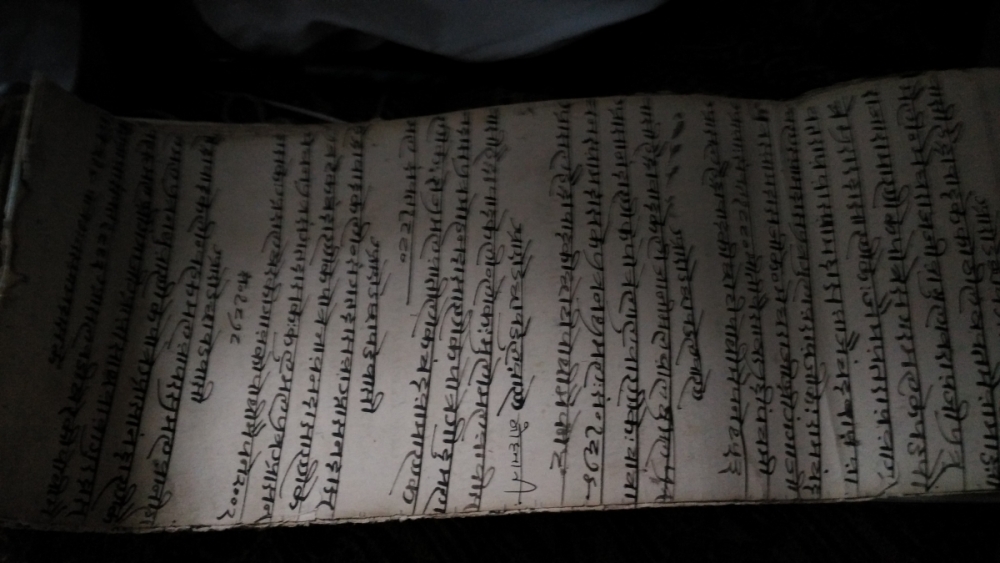

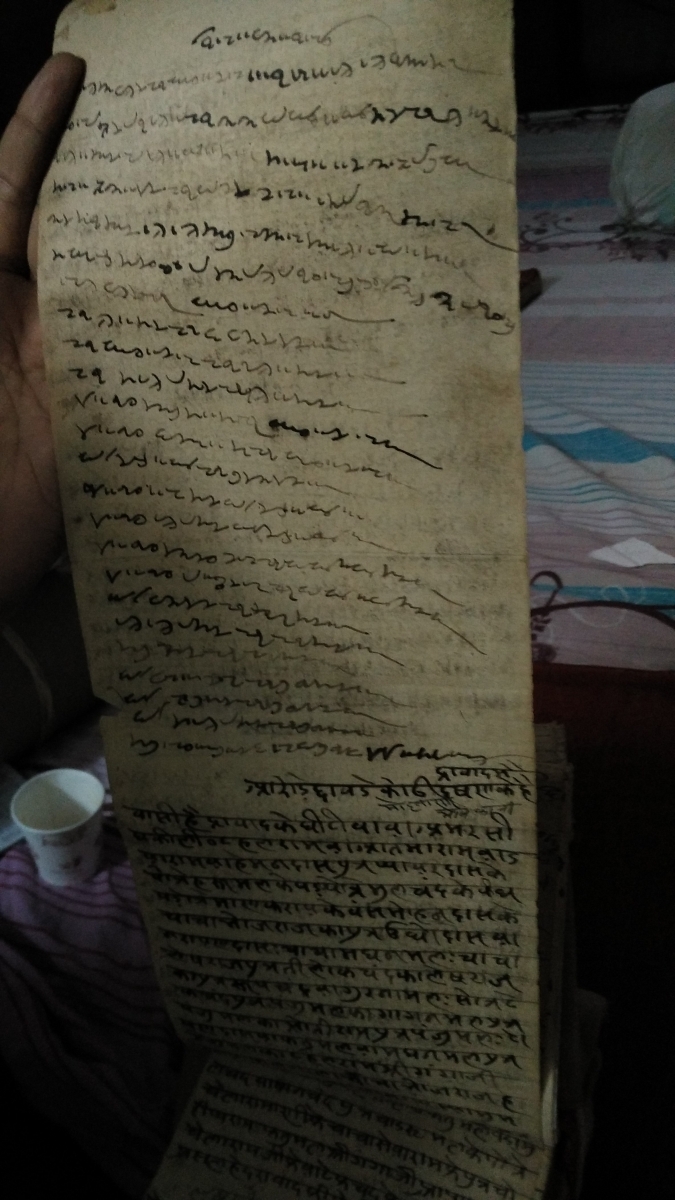

At Hardwar, I was able to locate our family priest, Pandit Balkrishna Sharma, and he showed me the ledgers that his family maintains of visitors to Hardwar. Pandit Sharma comes from a line of hereditary priests who perform rituals at Hardwar. Anyone who visits is invited to write in the ledgers, giving information about their families and the reason for their visit. Pandit Sharma showed me entries made by members of the Mohinani family. Starting from recent entries, we went back over the years and decades. People writing their names and the purpose of their visit would also mention the names of their male relatives. Using this information, we were able to keep going back in time, all the way back to the ancestor Mohan from whom we got our family surname, Mohinani. When Mohan died, his son Moolchand brought his ashes to Hardwar and wrote in the register, ‘From this day onwards, I and all my descendants will be known by the name Mohinani, in memory of my father Mohan.’ I took a photograph of this historic entry but to my great regret, lost it. In those days, digital photography was new and the photos of that trip all got deleted by mistake.

In the years to come I visited Hardwar a number of times and read my ancestors’ entries with fascination. It was an intensely emotional experience seeing their handwriting, the three different scripts (Sindhi, English and Hatvanaki) in which they wrote and their signatures, and trying to imagine the kind of people they were and the kind of lives they led. Some fascinating family stories emerged, and we were also able to construct our family tree. However, I never again saw the page with Moolchand’s entry though I searched for it on every visit and continue to do so. Many of the old papers have decayed and torn and are preserved in bundles of tatters. Some old entries have been copied on to fresh paper.

Once our family tree was complete, I decided to start another project: to make a directory of all the Mohinanis all over the world. One reason for this is that I would like to fund Mohinani youngsters without their own means through their education. I myself craved for an education but did not have the means to pursue it and I would like to support any young Mohinani who wishes to be educated.

The inner journey

As children, we never received religious instruction. Although we were never taught to say prayers, we knew that our parents were religious people. Our school in Tanjung Pinang was run by Catholic nuns. My friends were Muslims. In Medan, my grandmother and aunts had fixed prayer routines and we often visited the Gurudwara next to our school. In Pune we had a small altar in our house with images of Hindu gods.

Our elders never called us to sit and pray together with them, but the way they prayed was so sincere and heartfelt that it created the same sort of feeling in us. That’s the sort of feeling I have tried to pass on to my children and grandchildren.

My first exposure to the Radha Soami teachings was through my father, who was a devout follower of the Radha Soami spiritual movement. One day, on a visit to Pune, I asked him why he never went to the Dera at Beas to see the Master. His answer was very simple. He said, ‘I don’t really need to. I see him inside, every day.’ It was years later that I understood for myself that, with proper meditation, the master shows his radiant form to the disciple.

My father never talked much about it but every time I left to go back abroad, he would give me a Radha Soami book saying, ‘Read this whenever you get time.’ I gradually became attracted to the path, which preaches a high moral life and the daily practice of meditation. Other important aspects are giving up non-vegetarian food and abstaining from alcohol and intoxicants. Both my wife and I are devotees and we have been given ‘naam’, which is a process of initiation in which we learn the technique of meditation, sitting still in silence and listening to an inner sound to attain a higher state of spiritual advancement. We have both experienced an inner transformation and have committed ourselves to the cause.

My wife and I have faced our share of life’s tragedies. Through all the disappointments and through the everlasting sorrow of our daughter’s untimely death, the teachings have helped us to find solace and equilibrium. (Concludes)

___________________

Courtesy: Sahapedia

Click here for Part-I , Part-II, Part-III