Author discusses Ashrams, Asthans, Dharamshalas, Marhis, Maths, Mosques, Samadhis, Shrines, Temples and Sikh Darbars.

Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

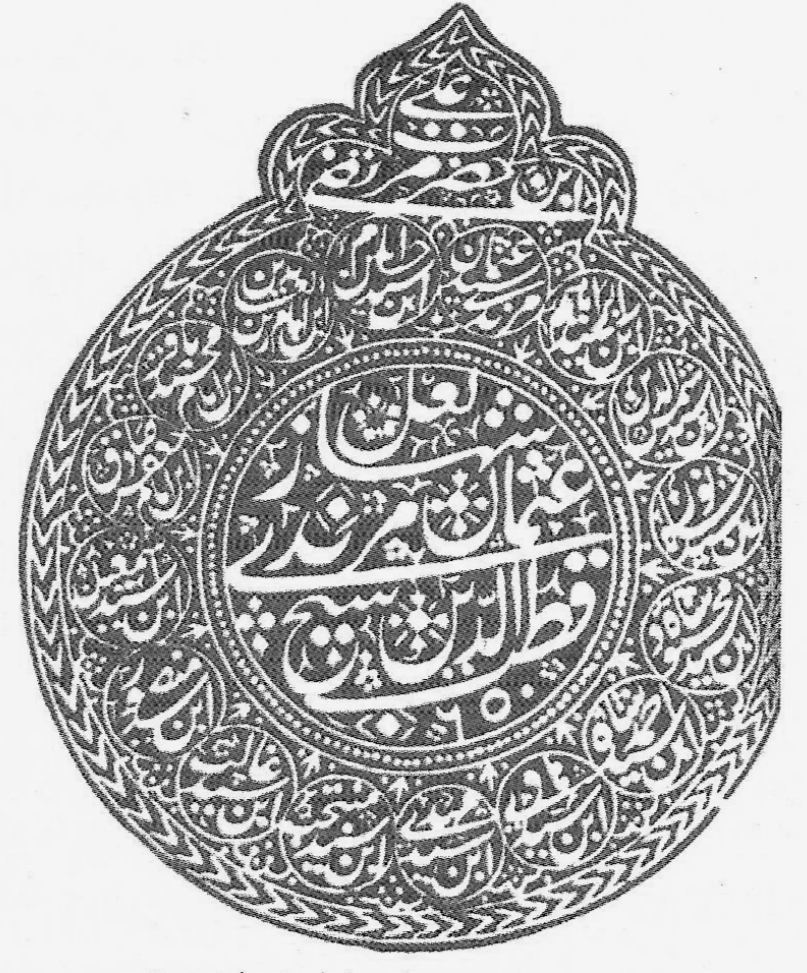

Makhdoom Mula Hassan

The landscape of Badin district is dotted with the shrines of Suhrawardi saints who were mainly the deputies and disciples of Bahauddin Zakariya of Multan (1170-1262). Many Sindhi ascetics went to Multan to study under Bahauddin Zakariya, and Sindh became the cornerstone of the Suhrawardi silsila from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries. Saints of various Sindhi tribes were given the religious title of ‘Dars’ – lesson – by Bahauddin Zakariya, after they had studied under him in his madrassah in Multan, and received the blessings and spiritual authority to continue preaching in their respective regions. The Sindhi Dars spread their teachings in every nook and corner of their own region and beyond, to Kachchh and Rajasthan too.

One of these was Makhdoom Mula Hassan, who became known for his piety in lower Sindh. With piety and comfort, he converted a large population of the Jats, a non-Muslim tribe in Sindh; a gentle conversion of faith using not force, but a love that transcended religious boundaries and caste barriers.

Makhdoom Mula Hassan’s teachings emphasized the values of humanity, tolerance, love, peace, equality and interfaith harmony, and the best example is one of his Hindu disciples who belonged to the Gurgala caste, whose members were never accepted or given equal treatment by upper-caste Hindus. When the Gurgala Faqir died, Makhdoom Mula Hassan asked his Muslim disciples to bury him near his Sufi lodge.

Makhdoom Mula Hassan is known as the patron saint of Jats, but his shrine is frequented by both Muslims and Hindus, and the grave of Gurgala Faqir is located at its main entrance. Devotees first pay homage to Gurgala Faqir before entering the main shrine. This was the way that the Sufi pirs taught their devotees to deal with the downtrodden and excluded members of society.

Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai

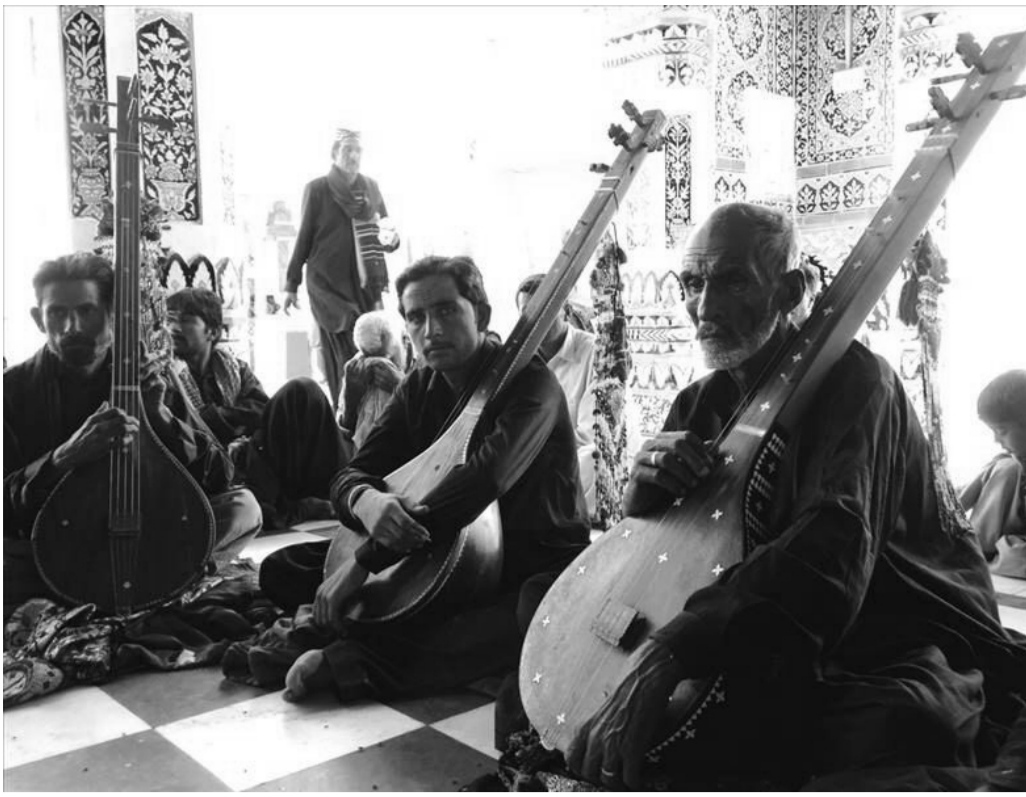

Morning or evening, at all hours of the day, the faqirs of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (1689-1752) dressed all in black, sit in a semi-circle before the door to his tomb, singing his poetry while the tamboura plays. The Shah jo Raag at his dargah enthrals the audience, who come from different parts of Sindh to pay their respects. This practice of Shah Jo Raag has continued unbroken since the days of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, when he himself sang with the faqirs.

The shrine complex of Shah Abdul Latif is always full of devotees, led by his faqirs who enter his dargah reciting his Sufi poetry. Many faqirs are to be seen leaning against the outer walls of the shrine and reciting his poetry. The Shah’s shrine provides succor to downtrodden segments of Sindhi society, who come to find solace praying, and sit leaning against the outer walls of the shrine which are decorated with blue and white tiles. Many of these are families of Hindus from marginalized castes.

The Shah Jo Rasalo has thirty surs; ‘sur’ refers to a mode of singing that corresponds to the subject matter. It was first published by a German scholar, Ernest Trumpp, in 1866 in Leipzig, Germany. More surs were later added by other scholars.

Shah Abdul Latif is known to have travelled with Hindu yogis to their pilgrimage centers in Sindh and Balochistan. In his poetry he also refers to popular Hindu sacred spaces in Kachchh, Girnar, Dwarka and Rajasthan, which he visited with wandering ascetics. Two surs of his Rasalo, Sur Ramkali and Sur Khahori, are devoted to yogis; in fact, yogis found a good place in the Sufi poetry of Sindh, being mentioned by previous Sufis also.

Shah Abdul Latif also utilized the main features of the folk romances of Sasui and Punhu, Suhni and Mehar, Umar and Marvi, Leela and Chanesar, Moomal and Rano, Nuri and Jam Tamachi, Sorath-Rai Dyachand Bijal, and others, to expound the spiritual journey undertaken on path to God.

Through Shah Abdul Latif’s poetry, these romances also inspired the Sindhi painters who painted scenes from them in tombs. All the folk romances that Shah Abdul Latif used in his Rasalo to convey his mystic thoughts became part of the later artistic repertoire of Sindhi painters – which they could draw upon to express their feelings and emotions in the form of murals depicting important episodes of the story.

In Shah’s poetry, women find a premier place. He reflects in his verse the suffering, sorrow and honesty of the woman of the land. In Marvi’s case, for instance, Shah depicts how her longing and love for her homeland were not changed by Umar’s wealth, affluence and luxury.

Shah Abdul Latif was born in the small village of Hala Haveli. He may have received a scanty formal education; his poetry, however, showcases his mastery of Arabic and Persian and his words, expressions and concepts have been absorbed into the Sindhi language and are integral to the identity of the Sindhi people. It is the mastery of his thought, and the new vocabulary he introduced, that led to him being described as the Shakespeare of Sindh. In every nook and corner of Sindh and beyond, Sindhis identify themselves as followers of Shah’s message of love, harmony, devotion and tolerance.

Sachal Sarmast

Daraza Sharif, a small village near Ranipur in Khairpur district is famous for Darazi dervishes of Sindh who trace their genealogy back to Hazrat Umar Farooq (RA), the second caliph of Islam, and are called Faruqis. From this Farooqi family of Daraza Sharif was born, in 1739, the great Sufi poet of Sindh, Abdul Wahab, who came to be known as Sachal Sarmast, the ‘truthful mystic’. Sachal also used the appellations ‘Sachu’ and ‘Sachidino’ in his Sindhi, Seraiki and Urdu poetry while in Persian poetry, his appellations were ‘Askhar’ and ‘Khudai’.

Sachal was against the rigid mindset of the clergy of his times, and this is reflected in his poetry. He was a great poet of the ghazal and the kafi, and invented new forms in Sindhi poetry as well as new traditions and styles of singing in music. His poetry continued to influence many of the later Sufi poets of Sindh.

The shrine of Sachal Sarmast is a symbol of tolerance, religious harmony, and social cohesion, where Muslims, Hindus and Christians frequently pay their respects. On his instruction, one of his chief disciples, Shamsuddin of the Khokhar tribe, travelled to Sikh shrines with a band of other faqirs. They spent time at the Golden Temple in Amritsar, and there he developed a Sikh following too. As a mark of his respect to the great Guru Nanak, Sachal affectionately renamed him Faqir Nanak Yousaf.

Sachal died in 1827 at Daraza Sharif. His tomb is believed to have been erected by Mir Rustam Khan Talpur, and it was later renovated and decorated with glazed tiles by a subsequent gaddi nasheen, spiritual successor. The tomb of Faqir Nanak Yousaf is situated in Agra village in Gambat taluka, Khairpur district.

One of the prominent disciples of the Darazi school of Sufi thought was Nimano Faqir (1888-1962), a Hindu woman. Born into a rich and religious Hindu family of Shikarpur, Ruki Bai became associated with the dargah of Sachal Sarmast after the death of her husband and was given the male name Nimano Faqir. Nimano Faqir preached not just in Sindh but also in Baroda (now Vadodara), where she established a Sufi lodge to spread the Sufi teachings of the Darazi dervishes.

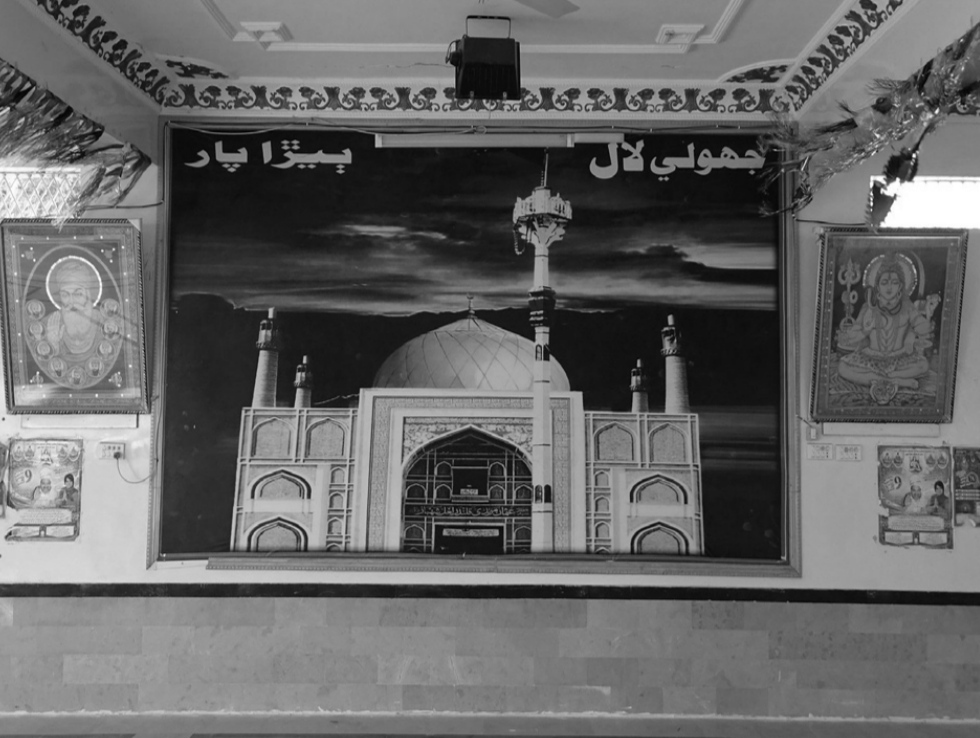

Jhulelal, also known as Shaikh Tahir

Sitting at the main door of the tomb, a Muslim devotee gestures to a Muslim woman to drape her scarf over her head. On the other side is the Hindu caretaker of the temple, gesturing to Hindu women to prostrate before the shrine. When I ask him which religion he belongs to, he smiles and confesses to a dual identity.

This is the tomb of Jhulelal, also known as Shaikh Tahir. Here both Muslims and Hindus worship in a shared space where the mosque and temple stand side by side. There are many such syncretic shrines in Lower Sindh, especially in the districts of Thatta and Badin, where both Muslim and Hindu devotees venerate the saints and lovingly acknowledge each other’s presence, carrying forward the centuries-old, shared heritage of Sindh.

The shrine of Jhulelal is located near Tando Adam town in the district of Sanghar, and takes the form of a walled complex containing a mosque, a temple, a domed well, and a shrine containing the sandals of Uderolal. The cult of sandals and footprints is common in many religious communities across the subcontinent, whether Jain, Hindu, Buddhist, or Muslim, who built structures over revered footprints as a mark of veneration. Jhulelal, also called Uderolal, Amar Lal, Darya Pir, Khawja Khizr, Zinda Pir and Shaikh Tahir, is a personification of the traditional Sindhi values of tolerance and harmony.

According to legend, Uderolal was born in Nasarpur, a town famous for ceramics and ajrak. The popular hagiography of Uderolal tells that he grew up to be a valiant and heroic man. It is believed that when Hindus were being forcibly converted by Mirkh Shah, the ruler of Thatta, he set out on his horse to save them. In another version, he rides out to Thatta on a palla fish on the water of the Indus. While the most popular depiction of Jhulelal shows him seated on a palla, another popular iconography shows him riding a horse and wielding a sword. The militant stance depicts his challenge to the despotic rule of Mirkh Shah, who turns out to be an imaginary ruler as his name is missing from the list of dynasts who actually ruled in Thatta between the thirteenth and the eighteenth centuries.

There is a possible interpretation regarding the fictional rule of Mirkh Shah: that it might have been a reference to the Sunni persecution of Ismailis, which took place at the hands of Ghaznavid rulers and governors in Sindh and Multan. Many of the Ismaili dars – preachers – in Sindh concealed their faith, preaching in secret and carrying dual identities to protect themselves from possible persecution.

It is interesting to observe that the term Jhulelal is also used for Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, a saint who himself carried dual identities – with Hindus calling him Raja Bharthari. Bharthari’s nephew Gopi Chand was also called Pir Patho by Sindhi Hindus. Pir Patho’s shrine is located 25 km from Thatta. Many Hindus in Tharparkar, especially in Diplo, have constructed asthaans or small temples dedicated to Pir Patho.

There are many shrines in Sindh where Hindu devotees take care of the shrines of Muslim saints. The Hindus have also built imposing structures over the simple graves of Muslim saints in many parts in Sindh.

Sadly, the tomb at Nasarpur, which marks the birthplace of Jhulelal / Shaikh Tahir, is now occupied by a family that has done some damage to the structure, and closed it to Hindu pilgrims. We have requested the Government of Sindh’s Culture, Tourism and Antiquities Department to rescue it from the occupants and convert it into a ‘Shared Heritage Museum’ where the artefacts of a pluralistic religious heritage could be displayed.

Lal Shahbaz Qalandar

The shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan attracts more people at its annual Urs than any other shrine in Sindh. The great saint died in 1274, and an imposing tomb was erected over his grave with a dome and other extensions added later. In 1994, it collapsed and was rebuilt in the second term of the late Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto as Prime Minister of Pakistan.

Many histories and hagiographies have been written on Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, with well-known books dating as far back as 1277 and 1357. These present his miracles, genealogy, spiritual initiation, travels, and his arrival in Sewhan. The information in them is predictably contradictory, and there is no consensus on which tradition he followed or who his spiritual mentors were. It is simply known that he was a great mystic and wandering Qalander of the thirteenth century, who led a celibate life, and there are many places in Sindh and Balochistan, takiyas, chilagahs, astans, kandas, khudis – basically small structures and trees – which mark his visits. It is believed that his name was Syed Usman, and that he was born in Marwand near Tabriz, so he was known as Usman Marwandi.

Popular tradition has it that he wore red garments, hence the name Lal. The following of Qalandar is so powerful that it transcends not just religious boundaries but boundaries of gender too. It is the only dargah in Sindh where, traditionally, not just men but women and hijras are also welcome to participate in dhamaal. Lal Shahbaz Qalandar was venerated under the name of Raja Bharthari by Hindus. Lal Shahbaz Qalandar is also believed to have been the lord of Bairagi ascetics and sometimes referred to as Raja Virag. Some ashrams of Shaivite ascetics have Lal Ji Khudi, small representations of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, usually posters and tridents.

The spiritual power of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar further manifests in the shrines of many of his disciples not just on the streets of Sehwan Sharif but in other parts of Sindh too. The earliest such shrine is located at Kanra village near Pir Gebi and was established about six hundred years ago. Another impressive shrine complex in Thano Ahmad Khan is about two hundred years old, but the first small structure was built in 1995 and it was later expanded to build an impressive dargah and other buildings in 2015. Its entrance is decorated with kashi tiles of Nasarpur, and the interior of the tomb is decorated with glasswork. Under the tomb lies the symbolic grave of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. An adjoining hall displays a poster of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar’s shrine at Sehwan, and the poster is flanked by an image of Lord Shiva on the right and Baba Guru Nanak on the left. Other shrines, Lal jo Kando, Qalandar jo Astan, and Lal ji Khudi, are located in the vicinity. These contain dhunis and tridents, and Qalandari dervishes and malangs celebrate and dance here also. The worshippers are both Muslims and Hindus. (Concludes)

_____________________

About the Author

Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro, PhD, is an anthropologist and assistant professor at the department of Development Studies at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad. This essay was collated by Saaz Aggarwal with extracts from several of his Friday Times columns, and includes excerpts from his forthcoming book Saints, Sufis and Shrines: A Journey through the Mystical Landscape of Sindh. Dr Zulfiqar has been exploring and writing about the less-known and unknown heritage of the subcontinent since 1998, when he was a student of Anthropology at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. Dr. Zulifqar is a ‘Khanani’ Kalhoro, descended from Muhammad Khan Kalhoro, son of Yar Muhammad Kalhoro, founder of the Kalhora Dynasty which reigned from 1700 to 1718.

All photographs in the essay were taken by him. He can be reached on zulfi04@hotmail.com.

The author has shared his article published in Indian scholar Saaz Aggarwal’s book ‘Sindh Tapestry- Reflections on Sindhi Identity: An Anthology’.

The author has shared his article published in Indian scholar Saaz Aggarwal’s book ‘Sindh Tapestry- Reflections on Sindhi Identity: An Anthology’.