Banerji had submitted a first report to Sir John Marshal on the discovery of Mohen Jo Darro in 1920 but the Marshal suppressed it and claimed having discovered the ancient site.

There is no mention of great archaeologist R. D. Banerji in any history book of Sindh and Pakistan. Even the antiquities department of Sindh is silent about him.

Nasir Aijaz

The Pakistani archaeologists and most of those from around the world had always been projecting the name of Sir John Marshal as the discoverer of the ‘Mohen Jo Darro’, the archaeological site of Indus Civilization in Sindh province of Pakistan, but never even mentioned Rakhal Das Bandyopadhyay Banerji, generally known as R. D. Banerji, a Bengali archaeologist, the actual hero who explored the ruins and had submitted detailed reports to his boss Sir John Marshal.

The historical fact is that R. D. Banerji had submitted a first report to Sir John Marshal on the discovery of Mohen Jo Darro in 1920 but the Marshal suppressed it and claimed having discovered the ancient site.

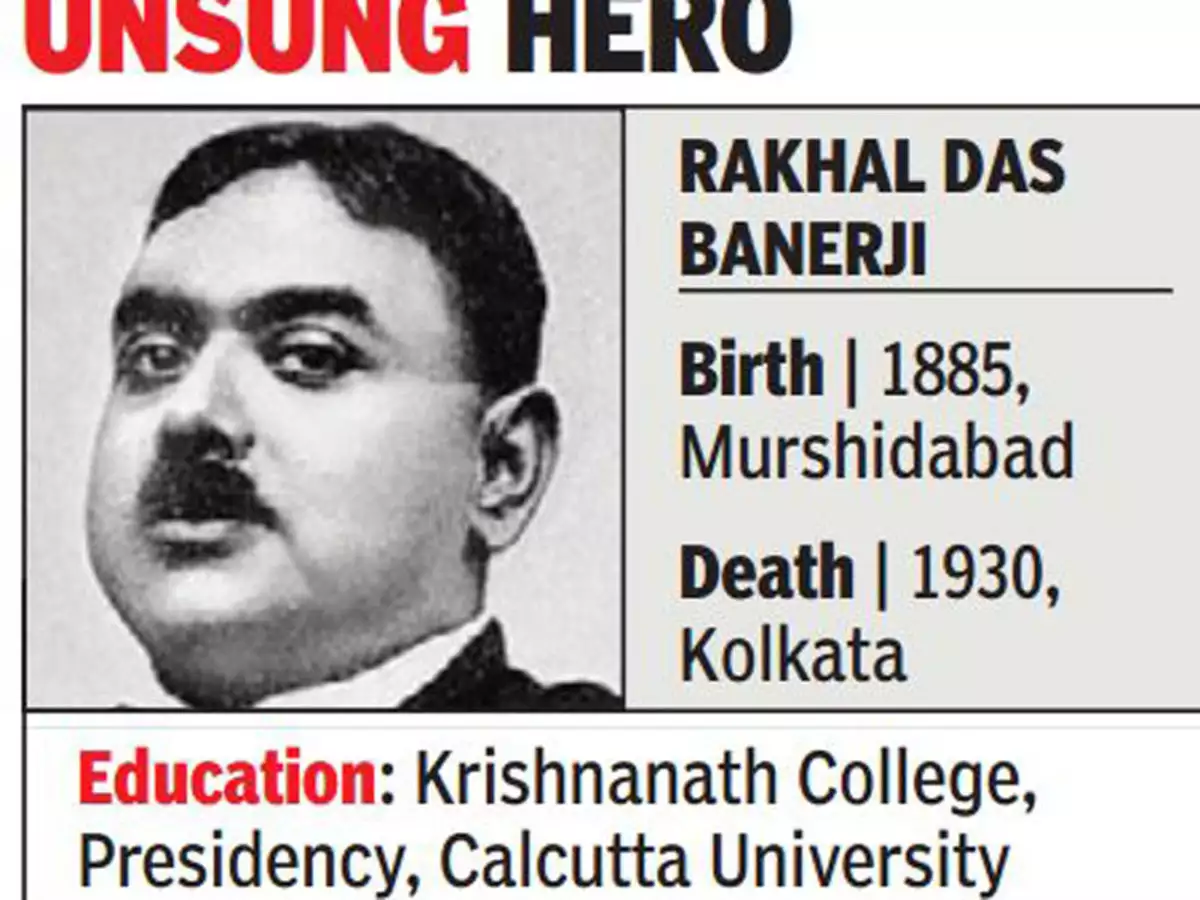

Unsung Hero

Unsung Hero

“It was a blatant theft of the credit for discovery of the Indus Valley Civilization,” an Indian author P. K. Mishra wrote in his book titled “Rakhal Das Banerji: The Forgotten Archaeologist” published in 2017. He had also delivered a lecture on the topic at Indian Museum, where talking to Times of India (TOI), he had said: “The accused is John Marshal, whose contribution to Indian archaeology is immense. He was the longest serving Director General of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) from 1902 to 1928.”

“The first report on the discovery of Mohen Jo Darro, submitted by Banerji in 1920, was suppressed by Marshal. So were the subsequent reports and the final one in 1922, which Marshal edited and used as the basis of ‘Mohen Jo Darro and the Indus Civilization’ – a monumental volume,” Mishra said according to a report with headline ‘Banerji robbed of credit for Indus findings’ published by TOI on June 12, 2017. The Indian newspaper published photograph of Banerji captioned as ‘unsung hero’.

Mishra remarked that ‘It was a blatant theft of intellectual property right, hard earned by a young Indian archaeologist, by his boss.’ “Records say that during 1918-22, Banerji carried out a five-season excavation at Moen Jo Darro. But the world knows that Marshal discovered the civilization’s ruins and it is taught in institutions. Banerji is just an insignificant footnote,” he pointed out.

On the basis of his research work on Banerji, the Indian author claims that Marshal didn’t know much about Mohen Jo Darro till May 1924. “He first visited the site only in February 1925. Marshal took direct charge of the excavation from winter 1925-26. By that time, Banerji had done all the work a discoverer should have done,” Mishra said.

Banerji had written to Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, another intellectual icon of the time – “See, they (The British government) will not allow me to publish anything on Mohen Jo Darro. But you can write something. I am handing over to you all the material I have and all photographs. You just write something on it and publish my interpretations. This may be a record for future generations,” Mishra’s book revealed, as reported by TOI.

Banerji had written to Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, another intellectual icon of the time – “See, they (The British government) will not allow me to publish anything on Mohen Jo Darro. But you can write something. I am handing over to you all the material I have and all photographs. You just write something on it and publish my interpretations. This may be a record for future generations,” Mishra’s book revealed, as reported by TOI.

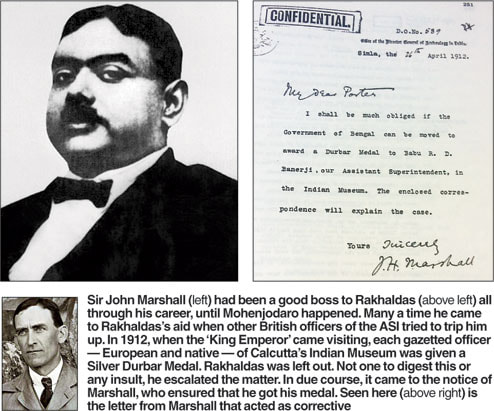

Banerji’s brilliance was recognized by British officers when he joined ASIA in 1917 as a 19-year old. He not only became a blue-eyed boy to Marshal, he was elevated to the post of superintendent of archaeology of Pune Division in 1922. But the final report of the discovery of Moen Jo Darro changed the color of this bonhomie. Marshal turned hostile. Banerji was shunted out to Indian Museum, Mishra writes in his book.

The Indian author Mishra’s remark that ‘Banerji was just an insignificant footnote’, is proved by John Marshal’s own words, who in second last paragraph of the preface to detailed reports published in London in 1931 under the title ‘Mohen Jo Daro and the Indus Civilization’, mentions the name of R. D. Banerji. Marshal, after acknowledging the role of British and other experts, states that ‘The other scholars whose names I cannot pass over in silence, are the late Mr. R. D. Banerji, to whom belongs the credit of having discovered, if not Mohen Jo Daro itself, at any rate its high antiquity, and his immediate successors in the task of excavations, Messrs. M. S. Vats and K. N. Dikshit.’

Although, for John Marshal, the name of Banerji was just to mention only in a few words at the end of his preface, the Bengali archaeologist was and is popular in India and Bengal for unearthing pre-Buddhist artifacts at the ruins at Mohenjo-Daro; for noting similarities between the site at Mohenjo-Daro and Harrappa. Those discoveries led to excavations at the two sites that established the existence of the then-unknown Bronze Age Indus Valley Civilization. His interpretations of this civilization, as desired by him, were published in a number of articles and books: “An Indian City Five Thousand Years Ago”; “Mohen Jo Darro” (in Bangla); Prehistoric, Ancient and Hindu India (posthumously published in 1934) and Mohen Jo-Daro – A Forgotten Report.

Another Indian author Asok K. Bhattacharya in his book titled ‘Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay’, published in 1999 by Sahitya Academy, India says, “Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay (R.D. Banerjee) is now a household name as the discoverer of Mahen (Moen) Jo Daro. As Superintending Archaeologist of the Western Circle he had gone to the Sind region in search of Greek pillars of victory and while unearthing the Buddhist Vihara surmounting the mound he came upon certain objects which reminded him of similar specimens found by Sahani from Harappa. He started digging in 1922 when the prehistoric remains were revealed. His interpretations and analysis about this civilization were published in a number of articles and books: An Indian City Five Thousand Years Ago (Calcutta Municipal Gazette, November, 1928); Muhen-jo-daro (in Bangla); Prehistoric, Ancient and Hindu India (posthumously published, 1934) and Mohen-jo-daro – A Forgotten Report (1984).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City, also researched and authored a paper on R. D. Banerji, how he found the ruins of Moen Jo Darro. He writes, “R. D. Banerji, an Indian archaeologist and ancient historian, was born Apr. 12, 1885. Banerji (also known as Rakhal das Banerjee and Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay) was working for the Archaeological Survey of India in 1920, surveying the lower part of the Indus River valley (now part of Pakistan), when he heard reports of a buried site surmounted by a stupa, a small hemispherical structure used by Buddhist monks for meditation. If the site were Buddhist, then it couldn’t be any more than several thousand years old. Banerji examined the area, made trial trenches, discovered seals and artifacts, and became convinced that a much older settlement lay buried under the mound. Later investigations proved him right. Banerji had discovered Mohen-jo-daro, the oldest and best preserved settlement of what we now call the Harappan Culture or the Indus Valley Civilization.”

“The city, still only partially excavated, and dating to about 2500 BCE, is quite impressive, made entirely of fired brick, with paved streets and a sewer system, and a large pool at town center. The stupa aroused Banerji’s interest. When Banerji began work there, everything below the stupa was buried. By 1925, an abundance of seals had been discovered, and a year or two later, wonderful art objects were turned up, such as a bust of a priest/king, and the now-famous Dancing Girl of Mohen-jo-daro. The ancient city of Harappa , 400 miles to the north, was being excavated at the same time, and it became clear that Harrapa and Mohen-jo-daro had a great deal in common and were part of a culture that pushed back the date of Indus Valley civilization by a full 2000 years, to around 2700 BCE.”

“The city, still only partially excavated, and dating to about 2500 BCE, is quite impressive, made entirely of fired brick, with paved streets and a sewer system, and a large pool at town center. The stupa aroused Banerji’s interest. When Banerji began work there, everything below the stupa was buried. By 1925, an abundance of seals had been discovered, and a year or two later, wonderful art objects were turned up, such as a bust of a priest/king, and the now-famous Dancing Girl of Mohen-jo-daro. The ancient city of Harappa , 400 miles to the north, was being excavated at the same time, and it became clear that Harrapa and Mohen-jo-daro had a great deal in common and were part of a culture that pushed back the date of Indus Valley civilization by a full 2000 years, to around 2700 BCE.”

The date usually given for Banerji’s discovery is 1922, so presumably that is the year he submitted a report to his boss on what he had found. That boss, the Director of the Archaeological Survey of India, was an Englishman, John Marshall, and he seems to have taken over the excavations at Mohen-jo-daro, while Banerji was shipped out to the Bengal-Assam region on the other side of India. He disappears from the Mohen-jo-daro record and ends up as professor of ancient Indian history at Banaras Hindu University in Uttar Pradesh, where he died in 1930, just 45 years old. There is some feeling among modern Indian scholars, and perhaps a little evidence, that Banerji has not received the credit he deserves, not just as the discoverer of Mohen-jo-daro, but as the person who first realized that the keys to understanding the ancient Indus Valley civilization lay there.”

“Mohen-jo-daro was named a World Heritage Site in 1980, which they spell Moen-jo-daro, presumably the Pakistani spelling. It is unfortunate that the lengthy citation nowhere mentions Banerji,” he concludes.

Again, a document at Ancient India section of British Museum says, “In about 1910-11, archaeologists from the Archaeological Survey of India visited the site near Dokri. They examined a stupa from the second century B.C. which stood high on a mound of bricks and earth. The archaeologists also noted many large mounds of earth covering a large area of ground.”

“Several years later, an archaeologist named Rakhal Das Banerji visited the site. Banerji believed that buried beneath the mounds of earth were the ruins of an old city. In the next few years, Banerji visited Mohen-jo-daro several times and began to believe that it was in fact a very ancient site.”

In about 1920 there was enough interest in the site of Mohen-jo-daro for the archaeologist Rakhal Das Banerji to excavate there. In the 1921-22 Season Banerji began his excavations.

In this first season Banerji’s team found the remains of a large city built mainly from baked brick. However, they did not know when it might have been built or who might have built it.

Banerji’s team found objects such as weights, beads and finely painted pottery. Perhaps the most important finds were small square seals like the ones found at Harappa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the document says.

Life sketch of R. D. Banerji

Life sketch of R. D. Banerji

Banerji was born on 12 April 1885 in Berhampore of Murshidabad District to Matilal and Kalimati. He passed his entrance examination from the Krishnath College School in Berhampore in 1900. Soon he married Kanchanmala (1891–1931), the daughter of Narendranath Mukhopadhyay. He passed his F.A. examination in 1903 and graduated from Presidency College, Kolkata with Honors in History in 1907. He obtained his M.A. in History from the Calcutta University in 1911.

Bandyopadhyay joined the Indian Museum in Calcutta as an Assistant in the Archaeological Section in 1910. He joined the Archaeological Survey of India as Assistant Superintendent in 1911, and was promoted to the rank of Superintending Archaeologist of the Western Circle in 1917. In 1924, he was transferred to the Eastern Circle and took part in the excavations at Paharpur. He took voluntary retirement in 1926. After teaching at the University of Calcutta, he later joined the Banaras Hindu University in 1928 and held the post till his premature death on 23 May 1930.

Bandyopadhyay’s first major independent professional work was in the fields of paleography and epigraphy. He won the Jubilee Research Prize of the Calcutta University for The Origin of the Bengali Script published in 1919 (and reprinted in 1973). He was the first to study the proto-Bangla script, the original form of Bangla script. He wrote the classic historical works on medieval Indian coins, and the standard works on the iconography of Indian art, in particular Gupta sculpture and architecture. His best known work was Eastern Indian Medieval School of Sculpture, published posthumously in 1933.

Works

Bandyopadhyay wrote two textbooks for Calcutta University, namely, History of India (1924) and A Junior History of India (1928). His The Age of the Imperial Guptas (1933) is a collection of lectures delivered by him in 1924. His standard two-volume Bangalar Itihas (History of Bengal) in Bengali (1914 and 1917) was one of the first attempts at writing a scientific history of Bengal. He also wrote two volumes on the history of Orissa, titled History of Orissa from the Earliest Times to the British Period (1930 and 1931).

His other significant non-fiction works include, Prachin Mudra (1915), The Palas of Bengal (1915), The Temple of Siva at Bhumara (1924), The Paleography of Hati Gumpha and Nanaghat Inscriptions (1924), Bas Reliefs of Badami (1928) and The Haihayas of Tripuri and their Monuments (1931).

Having published three novels, Pakshantar (1924), Byatikram (1924) and Anukram (1931), his other literary works in Bengali language were historical fictions. The setting of his Pashaner Katha (1914) is Kushana period. His three other novels, namely, Dhruba, Karuna (1917) and Shashanka (1914) are set in the different phases of the Gupta period. His Dharmapala (1915) narrates the story of the Pala emperor Dharmapala. Mayukh (1916) describes the Portuguese atrocities in Bengal during the reign of Shahjahan. Asim (1924) narrates the condition of Bengal during the reign of Farrukhsiyar. His last novel, Lutf-Ulla is set in Delhi at the time of the invasion by Nadir Shah. Another fictional work, Hemkana (incomplete) was published in Prabasi magazine from 1911–12. A number of his novels were translated into other Indian languages.

__________________

(Sources: Times of India, Linda Hall Library, Wikipedia, Peoplepill, Sir John Marshal’s book ‘Mohen Jo Daro and the Indus Civilization’ Vol-I, Rare Book Society of India, and other websites)

(Note: Different documents spell Mohen Jo Darro differently. Some spell it as ‘Mohen Jo Daro, some as Muhen Jo Daro and Mahen Jo Daro, but the proper spelling and pronunciation is Mohen Jo Darro)

(The article, mainly based on material available on websites, was prepared after a Sindh Courier reader from Bengal mentioned R. D. Banerji’s name in his comments a couple of years back on an article about Bengali archaeologist Mujamdar, who was assassinated in Sindh – Nasir Aijaz)