The fact is that most landowners in what is now Pakistan supported the British and were well recompensed for their loyalty.

Tim Willasey-Wilsey

The year 1857 is not widely recognized in Pakistan as an important year. Even its centenary was not celebrated. This is hardly surprising. The fact is that most landowners in what is now Pakistan supported the British and were well recompensed for their loyalty. Lands and titles were granted; a classic example being Mohammed Hyat Khan of Wah rewarded for carrying the body of the fatally wounded John Nicholson out of Delhi city to safety. He was made a Nawab; his son Sikandar was knighted and became premier of Punjab; and his grandson Shaukat a cabinet minister. Furthermore regiments of Punjabi and Pashtun Muslims from areas now in Pakistan played a significant role on the British side in retaking Delhi from the mutineers and thus saving the Raj for another 90 years.

All the famous episodes of the Rebellion took place in what is now India; the outbreak at Meerut on 10th May 1857 when the sepoys rose and killed several British officers and their families, followed by the seizure of Delhi and the siege of Lucknow, the massacres at Jhansi and Cawnpore and the eventual recovery of Delhi by the British. However some important events took place in what is now Pakistan. Uprisings in Peshawar, Lahore, Mardan and Nowshera were quickly suppressed by the Governor of the Punjab, Sir John Lawrence and the young Brigadier Nicholson. A ‘Moveable Column’ was formed under Nicholson to help retake Delhi, but this meant removing most of the British regiments from this area. In the circumstances it is hardly surprising that the sepoys in Jhelum and Sialkot seized their chance.

The Jhelum Mutiny is well told in a fascinating book of letters home by a young officer’s wife, Minnie Wood. The book, entitled From Minnie with Love is edited by Jane Vansittart. Poor Minnie Blane is swept off her feet in 1856 by a dashing Captain Archie Wood during his leave from India. Soon she is married and having to endure the four-month sea voyage to India with a husband she is quickly beginning to see through. Not only is Archie Wood heavily in debt but he is a weak, lazy man prone to self-pity and displays of violent anger. As if this were not enough Minnie, now with a baby, finds that Jhelum, their first posting, has nothing to recommend it, dusty, small and insufferably hot. She feels desperately cut-off from home, letters taking two months via Suez, Bombay, Karachi and Multan. Then the Mutiny breaks out. It is difficult to imagine the terror of being in Jhelum with perhaps a dozen other British families as news of the atrocities in Cawnpore and elsewhere spreads, often in lurid and exaggerated detail. There seemed to be no way out in any direction. The Grand Trunk Road (GTR) to Calcutta was blocked by the mutineers in Delhi. The route by river from Multan to Karachi and Bombay was possible if risky but Archie did not have the money for the fare.

In fact the reasons for the loyalty of most in what is now Pakistan is quite simple. The lands which now comprise Pakistan had been dominated by the Sikhs until the 1840s. To the suppressed Punjabi and Pashtun Muslims of the area the British were seen, for a time, as liberators.

Archie was convinced of the loyalty of his regiment but he was wrong. On 7th July it mutinied just before a detachment of the 24th Foot (an all-British regiment) came to disarm it. Wood just got his wife and baby to safety in time, but there was a whole day’s fighting in which the British troops came off second best as they tried to dislodge the mutineers from a fortified building in the town. Many of the 24th were drunk but fortunately for them the mutineers eventually fled in the night. Archie’s letters to his mother-in-law are an excellent and thrilling read, marred only by a somewhat panicky tone and his usual fixation with money.

Two days later the regiments in Sialkot mutinied. This time there was no 24th Foot to come to the rescue, and the British residents had a terrifying dash of some two miles to the old Sikh fort on the hill, their prearranged safe-haven. On the way several were hacked down by the soldiers including the Brigadier and Major William Bishop. Two medics, both called Graham, were killed in front of their families, and there are numerous other stories of tragedy and some of miraculous escapes. After a harrowing night in the fort the survivors learned that the mutineers had set off for Delhi. On 12th July the latter were intercepted by Nicholson and over the next few days annihilated. Savagery was not only practiced by the sepoys in 1857. Captured sepoys were blown from artillery guns!

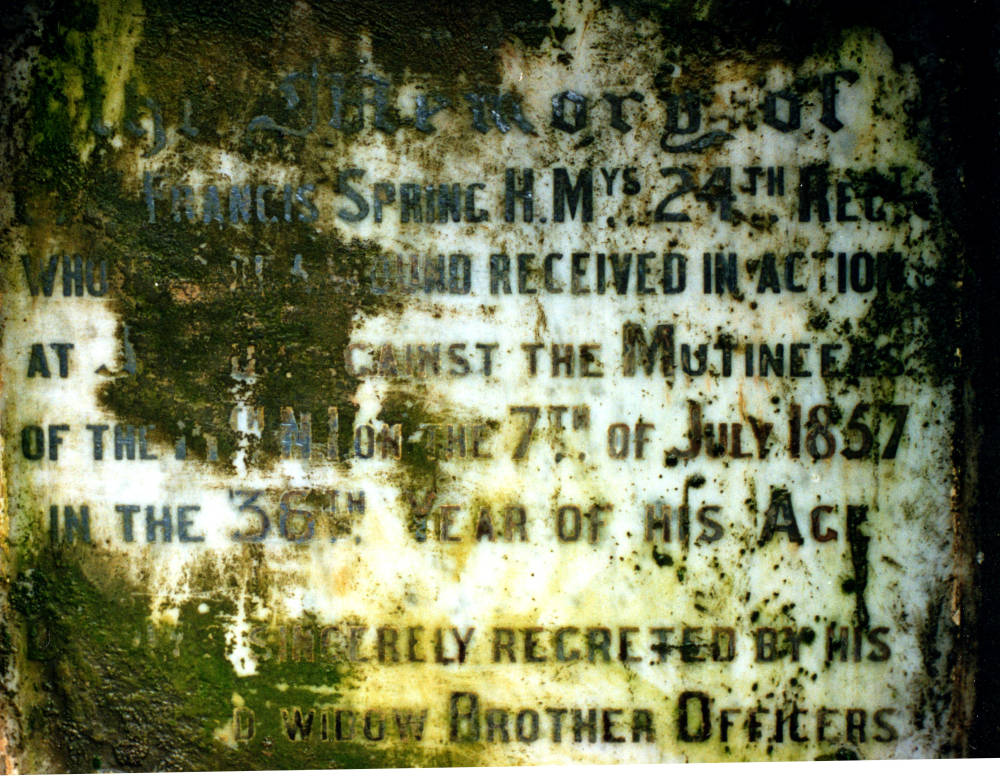

The two outbreaks can be retraced quite effectively today. In Sialkot the remains of the fort are still there and you can drive the exact route from the cantonment which those few families took that morning. Their graves are still at the foot of the fort mound and the two churches, Holy Trinity and the Catholic St James still contain memorial plaques. We learn, for example, that Bishop’s widow had also lost her infant son earlier in the year. Jhelum is even better for reconstructing the events of 7th July 1857. The rough sketches by Archie Wood can be matched with the town today. The church, St John’s, consecrated in February 1857, gives us another marker. The modern bridge was then a ‘bridge of boats’ in the same position and the cantonment ‘Centre road’ is still there. In fact the present sleepy cantonment, although much bigger, still retains some houses from the Mutiny era. So you can easily imagine the Woods’ hell-for-leather flight through a hail of bullets to the relative safety of Major Brown’s house. And after much searching I found the fortified building used by the mutineers, just to the north of the railway station. As in Sialkot the cemeteries have been vandalized but I located the grave of poor Captain Francis Spring, killed as he tried to urge on his drunken lads that scorching afternoon. A plaque to him and thirty-four other members of the 24th can be seen inside the church.

The historiography of 1857 is difficult for Pakistan. At various times since Partition historians have tried to interpret 1857 through the lens of 1947. One or other side has claimed to be the more “martial” or due more credit for the Subcontinent’s liberation struggle. In fact the reasons for the loyalty of most in what is now Pakistan is quite simple. The lands which now comprise Pakistan had been dominated by the Sikhs until the 1840s. To the suppressed Punjabi and Pashtun Muslims of the area the British were seen, for a time, as liberators. Furthermore the very best British administrators had been sent to the newly conquered territory. Known as “Henry Lawrence’s young men” they included John Nicholson, Harry Lumsden, Herbert Edwardes and James Abbott whose town in the Hazara area became briefly famous in 2011 for very different reasons; Abbottabad.

_________________

The author is Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Centre for Defence Studies, King’s College, London

Courtesy: The Victorian Web (Article was published in 2014)