“How would I know anything about Sindhi culture?” said Shakuntala’s cousin, and she asserted, “You should! Your blood is Sindhi, and you were born to Sindhi parents.”

Saaz Aggarwal

“Tina dear, the marriage ceremony begins at 11am, so you can have a little rest and then get ready.”

My niece Tina had arrived early that morning from Canada to spend a fortnight with us before she returned to her parents, and then on to the University of British Columbia to complete her graduation. When IRB and I picked her up from the airport at 3am, she happily announced, “Aunty, Dad said I must learn something about Sindhi culture from you. He says you know everything.”

I phoned cousin Kamal as soon as we reached home and gave him a piece of my mind. Never mind what time it was in Canada and whether or not he was busy.

“What instructions have you sent me through your darling daughter? I must teach her something about Sindhi culture? Firstly, you are shirking your own responsibility and secondly, courses in cultural studies are taught over a period of two years! There’s nothing I can do in two weeks!”

“You are the Professor, sis, and you know everything. I was born in Calcutta, schooled in Panchgani, flew off to Ohio for my graduation – Moved to Dubai to work for two years – Then to Hong Kong and Singapore. After that, as you know, I came to Canada and met my Bengali wife Mitali, born and raised in Toronto. How would I know anything about Sindhi culture?”

“You should! Your blood is Sindhi, and you were born to Sindhi parents,” I scolded him in as firm a tone as I could muster. For Kamal, two years younger than me, has always been like a younger brother. We had spent many happy days together while growing up in Calcutta.

“I’m sure in all the various places I have stayed in, my blood has got diluted. I will soon be heading for Texas as my Sindhi partner says the property market there is booming.”

“Before you go off to Texas, take time off to study and then teach Tina something about Sindhi culture.”

“Sis, I can’t take any time off! Don’t you know Sindhis are the original gypsies? And I am one such. It’s in my blood.”

“Ok, ok,” I said, quite amused, “as usual you have all the answers. You haven’t changed at all! But what shall I teach her?”

“My dear sis, teach her anything. Don’t you remember how you taught me to buy Sindhi mutton? Teach her that.”

“I don’t remember buying Sindhi mutton! And I don’t like going to smelly butcher shops. Anyway, I’ve become veg. What a strange thing to ask me to do. By the way is that a part of Sindhi culture?”

“Of course it is! It is part of our heritage. I was in New York in the Indian area at Jackson Heights, when a man came to the butchery and asked for ‘Sindhi mutton’! I thought the butcher wouldn’t understand, but the fellow smiled and replied, ‘Yes, of course sir. We have tender mutton chops cut the way Sindhis like’. He was obviously familiar with this special Sindhi cut and quality!”

“Well if that is all you want her to learn, then just take her to Jackson Heights on your next trip!” I suggested as helpfully as I could.

He continued as though he hadn’t heard: “I remember that day when Uncle, your dad, was not feeling well and he wanted to eat photay jo teevan. He felt it would be good for his sore throat. So we went to the New Market and I told the butcher: ‘Aadha killo mutton’ and he instantly packed up a parcel in a newspaper and handed it to me. You grabbed it and gave it back to him and announced authoritatively: ‘Bak-ree ka nahi, bak-ray ka. Ye jaldi vapas lo. Aur budhe bakray ka nahi. Chhote bakray ka. Aur chops kato!’

You were fourteen, and scrawny. And I was twelve. The butcher laughed shamelessly and stared at you, a chit of a girl, ordering him. You held your ground and refused to budge and pointed to the cut you wanted. Then without uttering a word, he unpacked the parcel and gave us the fresh cuts you had pointed at! When we came home, your dad said the mutton was better than anything he had ever purchased.”

“Kamal, you’re making this up. I don’t remember this incident.”

“Cook some photay jo teevan and send me some. Then you’ll remember. Also saee bhaji. A dabba full of each item, please!”

And he rang off.

_______________________

Courtesy: Saaz Aggarwal/ Sindh Stories

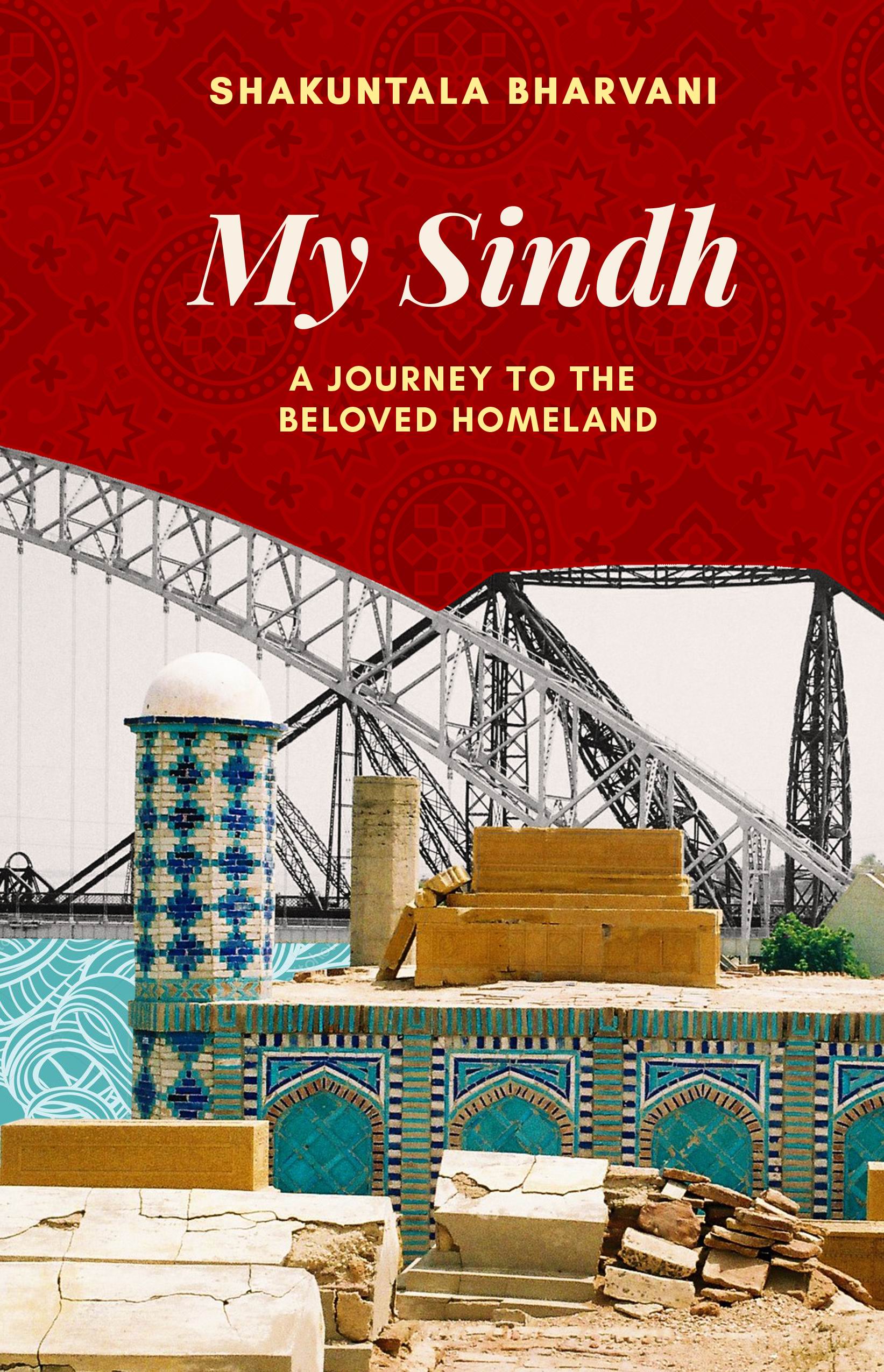

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.

Saaz Aggarwal is an independent researcher, writer and artist based in Pune, India. Her body of writing includes biographies, translations, critical reviews and humor columns. Her books are in university libraries around the world, and much of her research contribution in the field of Sindh studies is easily accessible online. Her 2012 Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland is an acknowledged classic. With an MSc from Mumbai University in 1982, Saaz taught undergraduate Mathematics at Ruparel College, Mumbai, for three years. She was appointed features editor at Times of India, Mumbai, in 1989.