There are few things more profoundly dead than an ex-empire, but around the time that the Soviet empire came apart at the seams, I became aware that the ghosts of a much older one – that of the Turkish Ottomans – were still haunting its former domains.

There are few things more profoundly dead than an ex-empire, but around the time that the Soviet empire came apart at the seams, I became aware that the ghosts of a much older one – that of the Turkish Ottomans – were still haunting its former domains.

By Nazarul Islam

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Ottoman Empire, for the first time was forced to recognize its full independence as a nation, not because of a war with a foreign power or an ambitious governor, but because of the aspirations of its own people. Many years later, at the start of World War I, the Ottoman Empire was often described as a dwindling power, mired by administrative corruption, using inferior technology, and plagued by poor leadership.

There are few things more profoundly dead than an ex-empire, but around the time that the Soviet empire came apart at the seams, I became aware that the ghosts of a much older one – that of the Turkish Ottomans – were still haunting its former domains.

It was in the spring of 1990. All Europe’s communist dominoes had already fallen over, the most recent being Romania, whose dictator Ceausescu had just been executed. The only one left standing was tiny, reclusive Albania. Every half-serious newspaper in Fleet Street wanted a bite of it, but foreigners were barred from entering – not only journalists, but even ordinary tourists. The only outsiders admitted were archaeology enthusiasts who were occasionally permitted to undertake study tours.

And so it came to pass that the next scheduled archaeological study tour was strangely over-subscribed. Of the 20 or so who signed up for it – claiming a range of occupations from farmer to advertising copywriter to ballet dancer – almost all were journalists, as our unlucky tour guide soon discovered. The exceptions were a clean-cut couple who turned out to be professional Christians, and four Pakistanis from Dewsbury. All six shared a common mission: to restore the faith – variously Christian and Muslim – to atheist Albania.

I had no idea that Islam had got as far into Europe as Tirana, let alone that its embers had survived being stamped on for many years by Enver Hoxha, Albania’s communist dictator. But it was in Albania’s grim and impoverished streets that I got my first whiff of the Ottomans: the beguiling reek of Turkish tobacco and coffee, the pungent kick of slivovitz.

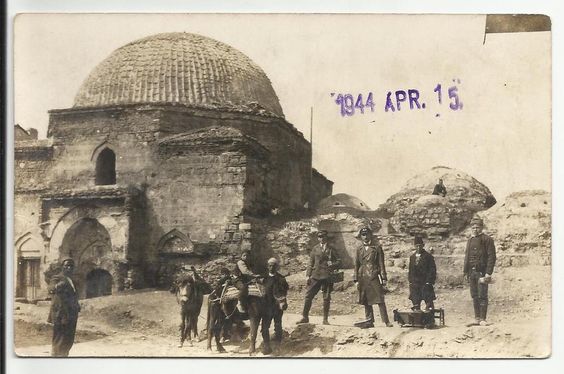

What we wrote about were the country’s modern hallmarks, the horrible housing estates and ubiquitous concrete bunkers. But what took one by surprise and lingered in the memory were the intricate old lanes of a town such as Gjirokaster, the compact but handsome old stone mosques built, one learnt, by colonizers from Istanbul for whom Albania was just as dismal a backwater as it was for us.

Albania was on the frontier, as much for the Ottomans as for the Russians and later for the EU. And as Eastern Europe slowly emerged during the 1990s from its communist purdah (veil), one discovered that the unique fragrance of Ottoman civilization lingered much closer to home. Greece, every corner of disintegrating Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, even Ukraine – all had been under Turkish control for centuries. They had been conquered and colonized by the Ottomans – by Suleiman the Magnificent (born 1492; died 1566) to be precise – before the English had gone anywhere.

And what really made us scratch our heads in puzzlement about that vanished empire is that, although the Ottomans were Muslims, and the figure we think of as the Muslim pope, the caliph, was identified with Istanbul, large populations of Christians and Jews continued to live and prosper right across the Ottoman Empire.

And what really made us scratch our heads in puzzlement about that vanished empire is that, although the Ottomans were Muslims, and the figure we think of as the Muslim pope, the caliph, was identified with Istanbul, large populations of Christians and Jews continued to live and prosper right across the Ottoman Empire.

After 150,000 Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, they were formally invited to make new homes inside the Ottoman Empire. True, the infidels faced higher taxation than the faithful, but for centuries, the Ottoman version of Islamic rule was distinguished by pluralism and peaceful coexistence. The now sadly beleaguered and diminished Christian communities of Syria and Egypt and Iraq bear witness to that.

Pan-Islamism was seen as a way to counter Europe’s colonialism, and presented the heart of Islam as outside of Europe’s reach. The development of other similar ideologies by the Empire’s rival, namely the Pan-Hellenism supported by the Greeks, and Pan-Slavism used by Russia to fight the Ottomans, also served to increase the influence of Pan-Islamism among the ruling Ottoman Elite.

___________________

About the Author